Hi folks, long time no see! This blog has lain dormant for some time, and I apologize for that, but sometimes life intervenes. This time, it took the form of my wife giving birth to a wonderful baby boy, not long after my last post. Now that I’ve finally found my footing as a dad (so. many. diapers.), I’m ready to get back at it.

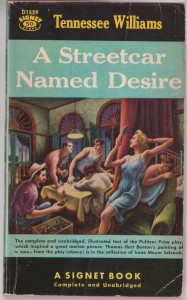

So enough mushy family stuff, let’s talk theatre history. I’ve just got a quick bit for this entry, based on two great paperback covers for a pair of Tennessee Williams’s best-known plays. First and foremost, they’re just cool: I mean, how many plays can boast of having a Thomas Hart Benton painting (more on that in a second) or Elizabeth Taylor (see below) on their cover?

The original Benton painting hangs in the Whitney Museum in New York. It was specially commissioned by legendary producer David Selznick, whose wife Irene produced Streetcar and contributed to its massive success. As the museum’s description notes, it conveys the tense, sexually-charged nature of the pivotal poker night, which lent its name to Williams’s original title for the play.

However, the detail that I find most interesting is the price: up in the top left-hand corner, you can see that this copy sold for 50 cents. Yes, it was a prize-winning play, but as this cover indicates, Signet was marketing Streetcar as a lurid paperback. As Louis Menand writes in this piece, mass-market paperbacks like this one proliferated in the post-war years, as highbrow and lowbrow literature alike were published in affordable editions and stocked “in wire racks that could be conveniently placed in virtually any retail space,” rather than a bookstore. As a way of catching potential buyers’ eyes, works like 1984 got covers that were just as eye-catchingly racy as those for titles like Hitch-Hike Hussy, and a prospective book-buyer might well find them sitting next to one another on one of those wire racks. Given this tendency to use sex to sell books, it’s hardly surprising that the erotically-charged Benton painting was used for the mass-market edition of Streetcar. Benton might be a major artist, and Williams could boast of a Pulitzer, but the ideal customer reaction that the publisher seems to have been looking for here was “Hm, this might be interesti- OH HEY NIPPLES!”

Then there’s this paperback edition of Williams’s later hit Cat On a Hot Tin Roof:

There’s a similar dynamic at play here in terms of sex; why else do you have a lightly-clad Elizabeth Taylor sitting on a bed? But the other notable thing about this is its reliance on the stars of the movie adaptation to catch potential readers’ attention. As Menand notes, part of the reasoning behind the rise of cheap paperbacks may have been to titillate customers into reading a book rather spending their time at the movies instead. At the same time, there seems to be an implicit admission here that movies had come to occupy a more prominent place in the popular culture than theatre. Ben Gazzara, the original Brick on Broadway, apparently just wasn’t going to sell as many copies as Paul Newman.

Both of these paperbacks are representative of the particular time and place in which Williams achieved his greatest successes. Few “straight” plays on Broadway today have the cultural currency that Streetcar or Cat had back then. Clybourne Park and August: Osage County are well-known, but I wouldn’t expect to see copies for sale outside of a regular bookstore. To my mind, this reflects the increasing fragmentation of our culture. A Broadway hit on the scale of Streetcar could dominate the attention of a more monolithic culture in a way that it couldn’t today. That’s not necessarily an entirely bad thing: I’m not the first to note that just about anyone who isn’t a straight, white male doesn’t have much cause to be nostalgic about many aspects of the 1940s and 50s. However, it is arguably reflective of the fact that theatre fandom has become, if not exactly a sub-culture, then only one of many options available to us in terms of art and entertainment.