Looking back on the 1930s and the rise of the illustrious Group Theatre, Harold Clurman remembered the allure of the Soviet stage. He recalled in his book The Fervent Years how Lee Strasberg would have a Russian acquaintance read translations of “newly arrived publications about the recent Soviet theatre,” an experience which felt to him and his compatriots “as if some tale from a new Arabian Nights were being told” (The Fervent Years, 91). The Group Theatre’s house playwright, Clifford Odets, sprinkled a few admiring references to the Soviet project throughout plays such Waiting for Lefty, in which the unjustly-fired Dr. Benjamin comments that he has dreamed about going to Russia for “the wonderful opportunity to do good work in their socialized medicine” (Waiting for Lefty and Other Plays, 28). Nor was Clurman’s circle alone in its enthusiasm for the Soviet theatre and the society from which it sprang: Hallie Flanagan, the main force behind the Federal Theatre Project, was just one of the many Americans who brought some of its practices back to this country.

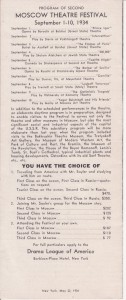

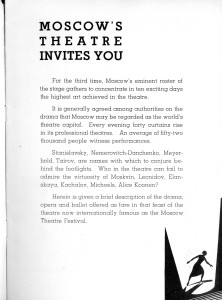

This fascination in the United States with the Soviet theatre is illustrated by the three pamphlets (a gift from my dissertation advisor) that I’m featuring in this blog post. They advertise the opportunity to take guided tours of the Moscow Theatre Festival (spelled “theater” the first year) in 1933, 1934, and 1935, respectively. On one level, they’re simply fascinating documents of the Russian stage, since the tours encompassed most of the significant theatrical movements in the country at the time. However, a closer examination of the content of these pamphlets (combined, admittedly, with the benefit of historical hindsight) brings to light some more disturbing truths.

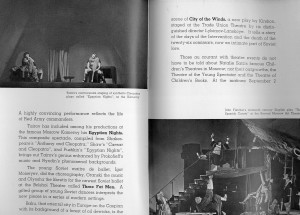

The tour offers prospective travelers a theatre-goer’s dream: the chance to see work by great directors such as Konstantin Stanislavsky, Vsevolod Meyerhold, and Nikolai Okhlopkov, among others. The glossy pamphlets feature fascinating images of many major theatrical figures and, most tantalizingly, production photos from the program on offer. The agendas for all three tours feature many productions at the Moscow Art Theatre, the famous home of Stanislavsky, who by this point had become a revered figure among American actors and directors, even though he hadn’t been at the cutting edge of Russian theatre for years. There were other attractions, too, such as the exoticism of Aleksandr Tairov’s Kamerny Theatre or the vaunted Russian ballet and opera.

Not all of the program was devoted to theatre, at least not directly. The first festival tour, in 1933, lists a lecture by Anatoly Lunacharsky as the initial item on the agenda. Lunacharsky had been the People’s Commissar for Education up until 1929, when he lost the job as a result of Stalin’s consolidation of power. Lunacharsky had a reputation for being pretty tolerant, since he’d done his best to protect edgier artists such as Meyerhold, but it’s still striking to me that the very first thing that the American tourists were scheduled to hear or see was a lecture on the Soviet theatre by the former official in charge of overseeing and regulating that theatre.

There are other items on the three tours’ schedules that don’t immediately relate to theatre. For instance, the agenda for September 9, 1935, is a “Visit to the Museum of the Revolution and other social institutions such as marriage and divorce bureaus, people’s courts and institutes for the protection of mother and child.” It’s pretty clear that there was an obvious motive on the part of Stalin to use these trips for propaganda purposes, and not only in the sense of showing off the theatrical culture of 1930s Russia.

The more that I examined these pamphlets, the more I noticed some details about what had been included on or excluded from the program. For instance, all three pamphlets prominently display Meyerhold’s name and photo, but his eponymous theatre only appears on one of the three tours’ agendas, in 1934. This seems a bit odd, given that he was arguably the single most important director of the Soviet era; the 1933 and 1935 pamphlets’ implied promise that tourists would get to engage with the man and/or his work at some point in their travels seems like false advertising. I should say that I’m no expert on Soviet theatre, so there may be extenuating circumstances that I don’t know about, but I suspect that Meyerhold’s absence from all but one of these tours has something to do with the fact that he was clearly in disfavor with Stalin throughout the 1930s, despite his best efforts to toe the line and create work that was acceptable to the dictator.

Other prominent theatre artists from the early Soviet period go completely unmentioned in this pamphlets, often for chilling reasons. For instance, none of them mention Vladimir Mayakovsky, the avant-garde poet and playwright who had a major impact on Soviet theatre in the 1910s and 20s but who then killed himself in 1930. Meyerhold’s productions of Mayakovsky’s last plays were a major reason that he remained in permanent disfavor with the authorities throughout the 1930s. Even more out-there, avant-garde artists such as Daniil Kharms, and other members of the OBERIU group to which he belonged, go unmentioned, and understandably so, since Stalin had Kharms arrested fairly recently.

By contrast, many of the productions that are in the pamphlets, while still exciting, are relatively tame. As I’ve mentioned, there’s a lot of stuff from the Moscow Art Theatre on offer. Part of this may have to do with Stanislavsky’s reputation in the United States, as well as the background of the person who led these tours. Stanislavsky was still a theatrical celebrity stateside, as his teachings inspired what would become known as Method acting. This was because most Americans hadn’t really had a chance to see his work until the 1920s, when he and the Moscow Art Theatre had toured with some of their best-known work, even though much of that work dated from 20+ years ago. Oliver Sayler, the leader of the 1930s tours, had been a major player in arranging for the MAT to come over to America in the 20s, so it makes sense that he’d focus on Stanislavsky and his organization. Much of what’s playing at the MAT and the other theatres in these pamphlets are productions of older plays from the nineteenth century, or even as far back as Shakespeare. Most of the contemporary plays on the programs are in the vein of Socialist Realism, which by this point had become pretty much the only approved style in the USSR.

Socialist Realism can work very well in the hands of a playwright such as Clifford Odets. However, despite his scathing, insightful critiques of the American society, and his occasional praise for the Soviet system, Odets was very fortunate that he got to live and work in the United States, because it allowed him to include all sorts of nuance that wouldn’t have been allowed in the USSR. Eventually, playwrights under Stalin became incredibly restricted in terms of what they weren’t allowed to do: there could be no hint of criticism of the Soviet system, and indeed plays were ultimately supposed to be “conflictless”, since to depict conflict within that system might imply that there was something wrong with it. It’s odd, but one of the things that I’ve taken away from my time reading some of the most representative of these plays is that, for all of the horror and misery inflicted by authoritarian regimes such as Stalin’s, their effect on art is to make it banal and boring.

Under the surface of these plays, though, something far darker is going on. The best example comes from one of the major Socialist Realist plays from this period, Nikolai Pogodin’s Aristocrats, which was performed by Okhlopkov’s vaunted Realistic Theatre for the 1935 tour. It’s a weird play: a comedy (in terms of genre, that is) about likeable petty criminals who become better people through hard labor on a canal-building project. It’s set during the construction of the White Sea Canal, a major project to effectively link the Arctic Ocean to the Baltic Sea.

Aristocrats is an especially chilling piece of propaganda, because it whitewashes a project that led to the deaths of thousands. Anne Applebaum’s book on the gulag cites estimates that about 25,000 people perished building the White Sea Canal (Gulag: A History, 65). Even for those who survived, the reality was bleak: the lovably mischievous criminals of Pogodin’s play were, in truth, often hardened thugs whom the prison authorities used to terrorize and keep in line the political prisoners who formed the main population of the gulag. The canal that so many died to build ultimately proved a white elephant, barely used and eventually falling into disrepair.

As far as I know, there were no more tours after the 1935 one. 1936 marked the beginning of Stalin’s Great Purge, when hundreds of thousands of people would be slaughtered in a paroxysm of paranoia and terror. Among the victims were artists such as Meyerhold, who was arrested in 1939 on bogus charges and shot early in 1940. The repressive atmosphere that silenced and destroyed individuals like him only grew worse, and it wasn’t until long after Stalin’s death that the Russian theatre began to show even a glimmer of vitality again.

The fate of people like Meyerhold, and the hidden history behind plays like Aristocrats, point to what I ultimately find so troubling about these pamphlets: they’re a tantalizing glimpse, for theatre lovers both then and now, of an intriguing period in the development of a particular theatrical culture that helps to elide the horrors of the Soviet era. I can’t help but be fascinated by the images and descriptions of the plays and experiences offered on these tours, and I assume that those who went on these tours felt the same way. With the benefit of hindsight, it’s easy to judge those people for buying into a system that led to the deaths of millions, but I worry that we’re just as susceptible to looking the other way when placed in situations like theirs. We want to believe that cultural events like the Moscow Theatre Festivals of the 1930s offer the hope of greater understanding between nations, but there’s always a risk that they will instead help to cover up the atrocities of those in power.